JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — Calais Campbell never talked about one particular six-month period just before he entered junior high school.

Not with his closest friends at South High School in Denver, where he was one of the country’s most sought-after recruits. Nor at the University of Miami, where he was one of the best defensive linemen in the nation from 2005-07. It was just too hard.

How does he bring up the fact that he and seven other members of his family spent six months in a homeless shelter? That eight of them crammed into one room in bunk beds? That they needed the kind of help that every family hopes they never will?

“I don’t think I really even told my best friends until I got to the NFL,” Campbell said. “So people that knew me very well, knew everything about me, didn’t know that part of me until I got to the NFL. It’s kind of one of those things that you didn’t really go around bragging about.

“I was very embarrassed about it, but at the end of the day I shouldn’t be because it’s a part of my life that really added a lot of character to me.”

Campbell no longer feels embarrassed. That short period, which happened when Campbell was 11, is one of the reasons he does as much work in the community as he has during his 10-year NFL career — first with the Arizona Cardinals (2008-16) and now with the Jacksonville Jaguars. It’s partly why he established the Charles Richard Campbell Foundation, which raises funds to help teach critical life skills to young people.

One of those fundraising events was held Tuesday night at Main Event Entertainment in Jacksonville. Campbell and numerous teammates — including quarterback Blake Bortles, linebacker Myles Jack, guard Andrew Norwell, and defensive tackles Malik Jackson and Marcell Dareus — spent several hours eating and bowling with fans, families and sponsors.

The Chandlers were one of those families. Seryta and Ellis and their two children, 14-year-old Aaron and 4-year-old Donovan, were guests of one of the event’s sponsors. Campbell spent more time with them than any other group for an important reason: They are exactly where Campbell was 20 years ago.

The Chandlers are one of the families that temporarily reside at the Sulzbacher Center in downtown Jacksonville. The four live in one room, at least until the homeless shelter opens a new facility just northwest of downtown that provides one- and two-bedroom permanent housing units. The Chandlers have been in that situation for nearly four months while they try to get back on track.

It’s not easy, especially since Aaron attends a junior high school that’s about a 40-minute drive away in a neighboring county. But the Chandlers are grateful for the help and stability, something they didn’t have at the beginning of the year.

“It’s hard not knowing where we were going to be at from day to day,” Ellis Chandler said. “Sulzbacher definitely took stress off of us. We knew that our boys had somewhere to go in the evenings. They were getting tutoring help and everything. … It’s been great being there.”

The Chandlers had been living with Seryta’s brother and his family in adjacent Clay County after moving to Florida from Maryland, but their hosts had to find another place to live and that left the Chandlers living in a motel. Ellis Chandler has been working at an Amazon fulfillment center since last September, but Seryta suffers from fibromyalgia and has been unable to find work, which meant money was tight.

Sometimes there wasn’t enough to pay for a room and the family had to sleep in their car.

“Our family and friends back home [in Maryland] would send money for a night’s stay and then if we didn’t have it we had to sleep in the car, which was heartbreaking for us with our kids,” Seryta said. “That’s when it just got to, like, we need to do something else.”

After a month in the motel the family reached out to the Sulzbacher Center and has been there since.

That stability was critical for the children, Seryta said. Especially for Aaron, who has been able to remain at Orange Park Junior High. He’ll be a freshman at Orange Park High School in the fall and plans on playing football; he is already working out twice a week there with the football team.

“We’re definitely doing much better,” Seryta said. “It helped the situation. Of course you’re always ready for something like your own [place], but it’s definitely a better situation since we’ve been at Sulzbacher.”

Eileen Briggs, the chief development officer at the Sulzbacher Center, said the Chandlers’ situation is not uncommon, but to see the way they’ve handled it has been inspirational.

“It’s amazing,” Briggs said. “We don’t usually have two-parent families. Most of our families are single-parent families and so to have the two-parent family intact is really great to see. The way that they’re able to care for their children and also take care of all the things that they need to take care of, they’re a very motivated family so they really want to do what’s right for their children. They just need a little bit of extra help.”

Campbell certainly understands that. That’s what his family needed when his parents Charles and Nateal both lost their jobs in the late 1990s. Both of Campbell’s older sisters were already on their own, but the rest of the family — Campbell, his parents and his five brothers — were forced to stay at a homeless shelter for six months until his parents found work again.

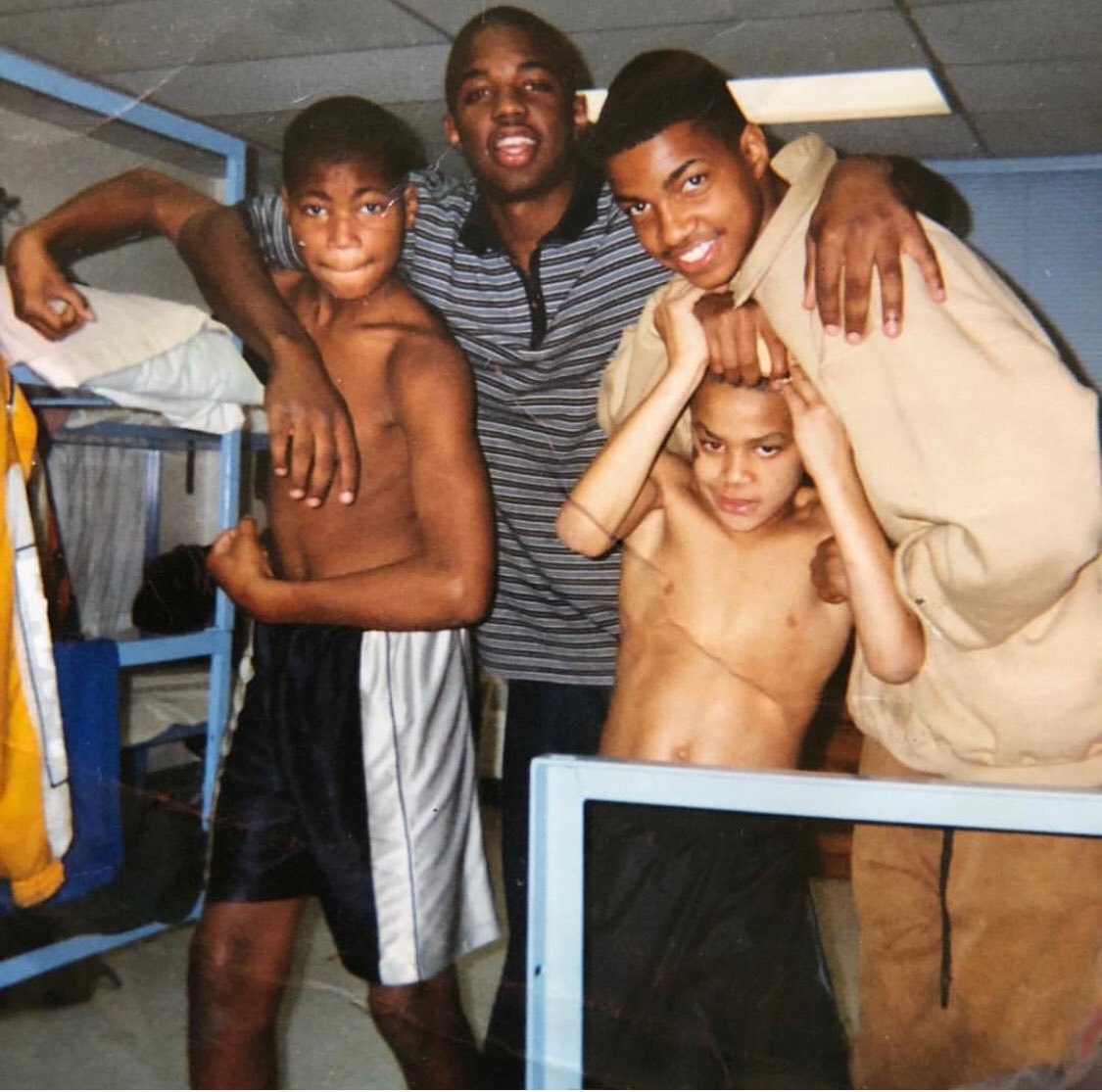

Campbell mostly remembers the closeness of that time — and not just because they all lived in one room. That’s why he is smiling in a photo taken from the shelter that he posted to his Twitter account on National Siblings Day last month.

“My family, my dad, my mom did a really good job keeping us together as a family, making sure that no matter how bad times were that we still had a lot of good memories and a lot of joy,” Campbell said. “The picture I posted that really got me talking about [it] was a picture of me smiling with my brothers hanging out. Because at that time we still had that great energy and that great family bond that nothing can separate.”

Campbell’s journey since then took him to the University of Miami and the Cardinals (as a second-round draft pick in 2008) and now the Jaguars, with whom he signed a four-year, $60 million contract with $30 million guaranteed in 2017.

Campbell has donated $1.6 million to Miami to establish an endowed scholarship for defensive linemen. His CRC Foundation, named after his father, has raised funds in Arizona and Jacksonville for things such as Christmas with Calais (Campbell and teammates take kids Christmas shopping), an after-school program and scholarships.

“I haven’t done nearly as much as I want,” Campbell said. “I really want to get involved in our youth and really start creating some life skills, and I really want to make a difference in our community. I’m just getting started, but it is important for me to really get involved. My father had taught me that you have to be involved in the community. There’s no reason to have a big platform if you’re not going to use it for good.”

That’s why he’s no longer reticent to talk about the six months his family spent in a homeless shelter.

“[It was] something I was embarrassed about most of my life until I got [to] the NFL and I realized that I should use it as a way to encourage the people who are going through times living in homeless shelters that they can be successful if they put their head down and work really hard,” Campbell said. “When you’re young and you get that kind of misfortune, it can be very tough on you. But at the end of the day if you get the hope and belief you can do something, if you see it happen, then it’s easier for you to overcome those odds. So for me, I really want to show that it’s possible.”